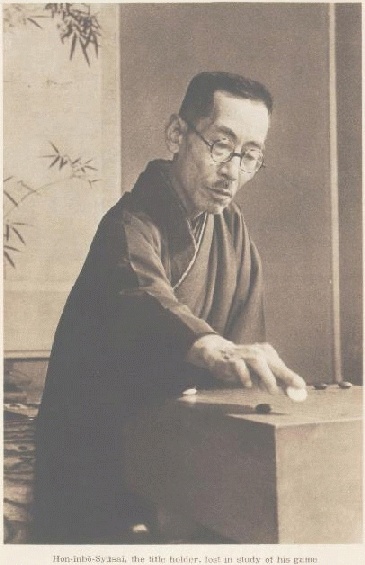

It’s already been eight years since Lee Sedol and AlphaGo had their historic five Go matches in Seoul, 2016. By now widely considered an iconic moment of contemporary culture, this game, marked by many portentous moments, carries the epos of a new technical and cultural moment. Sixty-two years earlier, Yasunari Kawabata was writing The Master of Go (1954). In this novel, first published in serial form for journalistic deliveries, the author tells of the match held by master Shūsai and Minoru Kitani, a young contender representing a new school and moment for the history of Go.

Beyond the match –more than a universe in itself– the representation of the players is resounding. On the one hand, their inexhaustible energy when it comes to playing, on the other, their relationship with the game tradition and new rules at the edge of the game itself.

The novel underlines the energy of the master not as demonic but as unhuman. The Go matches extend for hours, along many days, and at night the master would harass players to hold games of Shogi for fun, sometimes until dawn.

On the rules at the edge of the board, a recurrent example in the novel are the plays made through an envelope. At the end of each day the last player would place their play on an envelope to be opened the next day to carry on the game. The new generations would use these in a strategic manner, either to make the opponent uncomfortable or to win a night of analysis on a surprising move. These trickery are alien to the master, worried about the art in the board, completely absorbed, like he usually is when playing.

One of the most important characteristics –so far– of AlphaGo and many other artificial intelligences, has been their capacity to play over and over. The unhuman characteristic of the master is the mere nature of an AI program. While electricity –or energy– is pumping, the software can play again, and again, and again. At a speed simply overwhelming for our human rhythm.

Once inside the game, the narrative structure includes the players eventual loosing. This underlines both the repetition of gameplay and a new in media res beginning adding up to the story. Each time the player looses its lives, it is turned into a card that may be drawn in the next attempts. Now the player gets to improve—hopefully— its deck after every attempt, enriching what Jasper Juuls called graceful failure, and also faces the idea of being a new player continuing a bigger single game.

Many games and other cultural artifacts have already emotionally played with the idea of repetition through defeat. However, with the introduction of the interactive dimension of video games into the rhetorical realm, I am sure there will be new interesting devices coming out of it in the future.

Though it is not much considered, the history of humanity is also a history of repetition. To play one more game, to draw again the failed circle, to play the sheet once more, to write a second version. Mastery and repetition are usually hand in hand.

I’ve been playing chess online for the past five months. I do it free of any professional pretension. In that time, I’ve played twenty-two hundred and thirty-two blitz matches, no increment, in what is equivalent to nine days, nineteen hours and thirteen minutes. In that time, I’ve reached about a thousand and forty ELO rating. Some would think I got obsessed, an algorithm would think I have a design failure that makes me restart every once and then.

We know machines use every piece of rule to achieve their task as precisely as possible. Would they use psychological trickeries to unbalance their opponent? How would this trick be if the machines were playing each other? At the end, the questions remain. From now on, how will the history of repetition be written? How, the history of agon and struggle?