Book Review

The first written record we have of the word αὐτόματον is in Homer’s Iliad. As we enter the workshop of Hephaestus, the Greek god of invention and craftsmanship, we see a flock of golden maidens moving around, especially built to assist him. They all have the knowledge and abilities of the gods to assist the divine inventor in his many wonderful creations. How could the mythical creative mind of the Greeks project such a far-fetched technology from the dawn of history? What materials fed such foresight tales so they could be conceived in the first place? What access do we have to the mysterious hinges between the materials of consciousness and speculative fiction that nurtured these stories?

Gods and Robots, by Adrienne Mayor, addresses the fundamental role of technological devices in many of the classical tales of the Greeks. Crossing borders to Italy, India, and China, we get a grasp of how these ideas and pieces of knowledge traveled throughout the ancient world. Western Robots guarding the relics of the Buddha were supposedly deactivated by King Asoka, who had known diplomatic exchange with Ptolemy II, who oversaw the scientific and literary heights of Alexandria during the 3rd century B.C. The ruler of the Egyptian city held fantastic processions with a 15-foot automated Dionysus leading a list of machinery.

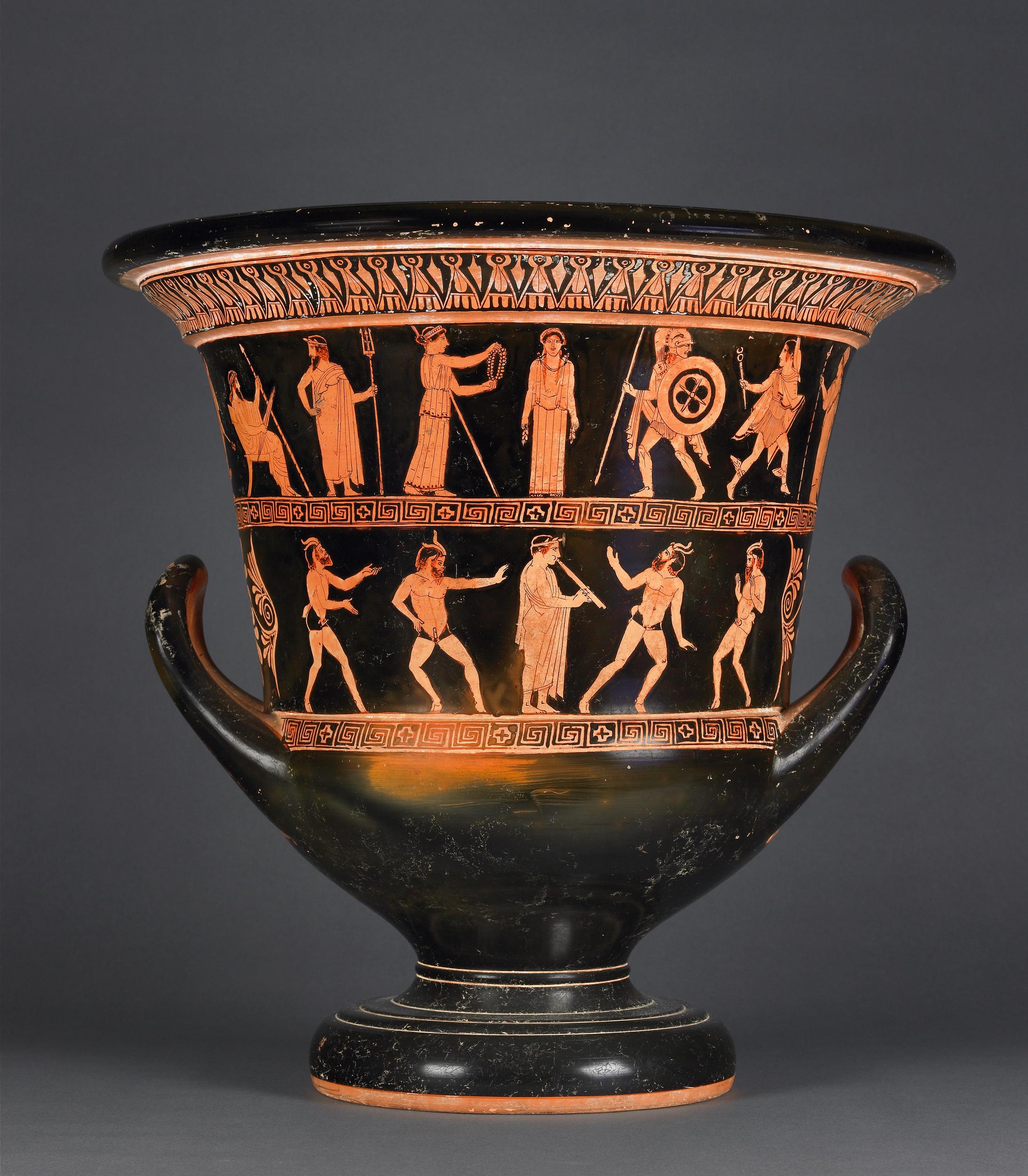

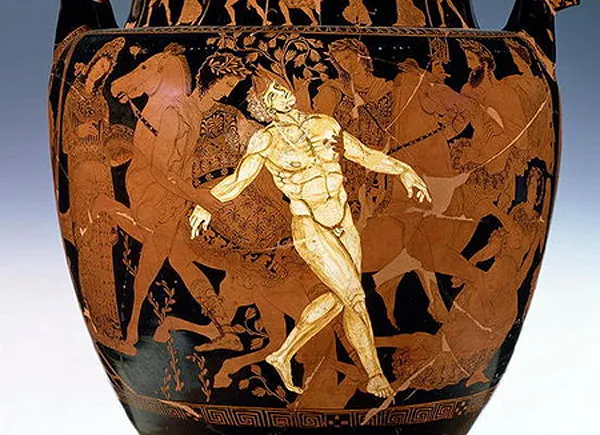

Adrienne Mayor shows a beautiful thread between the material technology and techniques used in antiquity – the analysis of vases and archaeological material is both beautiful and informative—and the speculative devices used in the mythological imagery of the Greek culture. It’s a wonderful achievement of the book to display the lost relation between ancient technology, mythology, and science. Much of the materials are now lost, and we can't but to wonder about the manuscripts with inventions and tragedies now lost to time.

The myth of Talos is probably the most iconic account of this thread. Talos was a giant automaton made of bronze, created by Hephaestus to protect the island of Crete. The myth tells us how the god of technique made him with a single vein of ichor, the divine blood of the gods, running through his body. Talos, probably imagined on the bases of the Giants of Mont’e Prama, was a guardian, a protector, and a symbol of the power of Haephestus technological devices. According to Apollodorus, the death of Talos was caused by Medea, who tricked him into removing the protection that kept his ichor inside. Talos basically was programmed with a bug. However not any bug, but the most human of them. Medea promised immortality to the giant, the rest we know.

I only felt one important question was overlooked. The book relies on the distinction of characters made, not borne. However, it doesn’t address the problem of Hephaestus, who was both made and born. The god of technique, the mythical father of almost every automaton of the ancient world, is himself placed in the middle of this division. Not only this, but right after Apollodorus tells us of the god’s nature, the author writes how the god cut Zeus’s head so he could cure him from a terrible headache, a bloody omen for the ‘father’ of that which was both made and born.

The work of Adrienne Mayor is a must-read for anyone interested in the cultural and scientific history of AI. With exquisite literary care, Mayor guides us through the archaeological and literary remains of the ancient world. We see our same wonder, our same hubris, the same humanity wondering what it means to be a robot and what it means to be human.